|

Ethnicity, Religion and Politics in Northern Nigeria

Quote: "Where does the ethnic conflict begins and stop and where do the religious conflicts begin and stop? Is it necessarily a fight between Christians and Muslims when two ethnic group clash and they happen to adhere to different religions?"

By Clement Stephen Dachet

Religion has been a major element that defines the northern part of Nigeria. The region is predominantly Muslim, and the non-Muslims are in the minority. Islam's influence of the north has been strong since the ascendancy of the hegemony of the Hausa-Fulani in the Northwest and in the Northeast, the rise of the Kanem Borno Empire of the Kanuri since the 1500s. Islam has not only established itself as a religious stronghold in the north but has become what shapes and defines the economical and socio-political nuances of this region. With such a posture of strength in the region, non-Muslims have always felt marginalized and alienated from the scheme of society's affairs and the fight for self-actualization has been an ongoing battle for the ethnic minorities of the north.

The non-Muslims of the north, although with on a few in the far north, live in the region of Nigeria popularly known as the Middle-belt; a name that describes its central placing in the country as well as defines its political quest for self-identity and actualization. It is unique by its composition: a very heterogeneous region of Nigeria with several tribal and ethnic groups. In fact, it has over half of the almost three hundred ethnic groups of Nigeria. In some cases, it takes a journey of less than a hundred kilometers to drive pass dozens of ethnic and tribal groups distinct from each other by full or a slight linguistic tone and accent. This region is undoubtedly the most ethnically diverse region of Nigeria.

While the diversity of this region remains a major feature that makes it unique, defining it as an entity or a part of the larger northern Nigeria has been a big challenge. For instance, the question of what defines the north will run along many fronts like, religion, language, ethnicity, and culture. When the reality of the diverse nature of the generality of northern Nigeria is brought into the equation, the true drama begins. It ends up being impossible to have a generally satisfactory definition of the north without having some part of the north feeling alienated or aggravated. Historical realities bear testaments to this.

The Herdsmen/Farmers conflict

Who are the Fulani people?

The Fulani are predominantly pastoralist who speak the Fulfulde. They are said to come originally from Senegal and today are spread across West Africa in Mali, Niger, Chad, Cameroun and the Central Africa Republic with their highest concentration being in Northern Nigeria. Not all Fulani’s are pastoralist. There are those who have long given up the pastoralist lifestyle, settled in cities and having a high level of education. However, those that remain pastoralist do so as the predominant way of life moving across West Africa in search of greener pastures for their livestock.

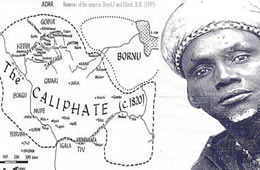

The Fulani are predominantly Muslims and in the history of Islam in northern Nigeria, they (through the famous Islamic scholar and Jihadist, Othman Dan Fodio) were instrumental in both the revival of Islam and its spread in what is termed the Fulani Jihad of the 1800s in the Hausa lands. This jihad saw the establishment of Islam as the religion of the region, bringing all its citizens under one leader of a new religiopolitical order, the Sultanate of Sokoto. Although this region is originally the home of the Hausas, the Fulani were able to assert themselves over the Hausas, both religiously and politically. Conversely, the Hausa language remained impenetrable that despite the Fulani Jihadist conquest, it has remained the main language of communication. The mixture of religion, politics and culture in a form of mutual assimilation of both Hausa and Fulani forge a shared identity such that one speaks of Hausa-Fulani’ as though they were a people.

Who are the farmers?

The people of northern Nigeria are historically farmers. The Hausas, although tied in religion and culture with the Fulani are traditionally farmers. The Kanuri and the Shwa Arabs of North East Nigeria, the diverse tribes settled in the Middle-Belt or central part of northern Nigeria are all agrarians. The Middle Belt region which is a savannah area is highly productive for agricultural activities, giving the peoples of the region a comparative edge to be a major food production region in Nigeria. The people of the central part of Nigeria were predominantly non-Muslim despite the advance of Islam in the 1800s. The peoples adhere mostly to their traditional religious beliefs and practices. This is not to suggest that they had no encounter with people from the far north. They did but it was not always cordial. The tribal people, as people of the middle belt were referred to, had always resisted the incursion of Hausa-Fulani religious and political domination.

During the close of the 1800s, Western Missionaries arrived with the goal of Christianizing the north of Nigeria. During this time, Colonial presence was well established in the North. The British, in 1903, had defeated the Islamic Caliphate of Othman Dan Fodio in the North and named it as its protectorate. Unlike the other Colonies, the British ruled the North through the already established sultanate and Emirates, thus what is known as the indirect rule: a system of control through pre-existing local power structures for taxation, communications and other matters.

Mission met resistance both from the muslims and the colonial authorities

Consequently, despite the enthusiasm of Missionary enterprises to bring Christianity to the far North, they met resistance both from the Muslims and from the colonial authorities who had a vested interest. With such an iron curtain to evangelize among the Muslims of the North, the Missionaries directed their missionary efforts towards the small tribes across the north-central region whom the Colonialist had basically little concern for. They were mostly regarded as pagans, uncivilized and savages—a derogation that meant the Hausa-Fulani had more respect than the small tribes of the Middle-Belt region.

The nomadic culture of the Fulani meant that they always travelled across the region in search of grazing fields, while the farmers of the middle-belt region settled in the fertile Savannah of the region, which was an irresistible attraction for the nomads to take their cattle in search of grazing areas. As such, the encounter between the pastoralist and farmers is an age-long reality. The conflicts that have emerged out of this encounter are not new. It is deeply rooted in their shared history.

Historically, such conflicts occurred in instances of trespassing, where a herdsman, knowingly or unknowingly, allowed their cattle to graze into the fields of the local farmers. There were, in most instances, established ways of resolving such conflicts through some sort of compensation (e.g. the herdsman giving a calf in return for destroying a farmer’s crop).

Changes in the socionomic matrix

However, over the years, as society ‘advances’, human activities of urbanization, deforestation and a combination of natural causes such as desertification and the drying-up of rivers and lakes in the far north, as in the case of the famous Chad basin that sustained several communities over the years, further shrunk available resources. These realities have changed the socio-economic matrix of the north. The northern part of Nigeria today accounts for the highest percentage of the poor among the regions of Nigeria. Certainly, there are both religious and cultural realities that have aggravated the situation in the far north to the low level of literacy, high level of unemployment and the abusive roles of the political and religious elite in the region that have created a perfect ground for underdevelopment.

Owing to these realities, there have been increased social disorders in the form of criminal activities masquerading as the quest for reclaiming a lost caliphate. The uneducated and unemployed youth are rife for recruitments as political hoodlums, terrorist and criminal bandits, thus creating havoc across the region. There have been increased robbery activities and kidnappings of persons for financial ransoms and the rustling of cattle mostly belonging to the Fulani-herdsmen.

Regarding the environmental changes in the north, as desertification pushes hard into once green areas in the north, the herdsmen have also pushed further south in search of greener pastures for grazing. It is not only the environment that has created these new dynamics. Urbanization has changed the course of traditional grazing routes used by the herdsmen for their nomadic sojourn. In the recent past, the nomads have begun to travel to the southern region of Nigeria, beyond the middle-belt, an area they usually don’t travel with their livestock.

A marriage of politics and religion

Politically speaking, since the religiopolitical campaign (Jihad) of Usman Dan Fodio, in the wake of the 19th century which led to the establishment of the Sultanate in Sokoto, Islam has sought to establish itself as the religion of the north, seeking to enforce its beliefs in every area of society. This is premised on the fact that Islam makes no separation between religion and politics or the state and culture or tradition. Political leaders and traditional rulers in the north have seen their roles as that of upholding and promoting the course of Islam. There has not been any better proof of this than the efforts made by State Governors and other political leaders in the northern States of Nigeria to enforce the Sharia legal system in order to achieve the realization of Islamic statehood. This negates the provision of the constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria which provides for a secular state and the freedom of worship for all Nigerians. However, the dominance of Islam in the North has led to the declaration of some states as Islamic with little or no regard for the non-Muslim population, who are equally citizens.

The far north/ The Middlebelt

Unlike the middle belt, the far north has common languages which bind its peoples together. For the people of the Middlebelt, the Hausa language is simply a second language. This common language and religion in the core north has helped create some level of unity and makes the presence of any other religion a threat to Islam and by extension the Hausa-Fulani’s firm grip over the north for political and social relevance. The middle-belt is the area among the other northern areas with a sizable population of Christians who although divided by ethnicity are united in their newfound faith identity, Christianity.

Time for an honest and just reflection

The so-called herdsmen/Fulani conflict, in my opinion, reflects unresolved questions. These questions are key to any honest discussion of national unity at any level of the Nigerian society. The crisis is not the main problem but its symptom namely that of a failed governing system to administer justice and fairness. Religious and ethnic coloration has rendered the delivery of these two impossible.

While there have been crises along religious lines, they have also always had ethnic undertones with them. Within the Middle Belt region, there have been clashes in the past that owe to ethnic sentiments. For instance, there is a long history of conflict between the Jukun and Tiv ethnic nationalities, both found in the Middlebelt, both are majority Christian, but have had a recurring conflict over land ownership. Another example is the conflict between the Kataf people of southern Kaduna and the Hausa Fulani, one a predominantly Christian ethnic group and the other a Muslim. The logical question to draw out of these two scenarios is: Where does the ethnic conflict begins and stop and where do the religious conflicts begin and stop? Is it necessarily a fight between Christians and Muslims when two ethnic group clash and they happen to adhere to different religions?

Identity and identification

Despite the fact that the nation called Nigeria was formed by bringing peoples of diverse cultural and religious affiliations and allegiances together, the change from an exclusive self-identification by the different peoples' groups did not die with the birth of a new nation. The fact is that being a Nigerian is the last of many layers of identities one holds to. My brother-in-law told me a story of a European missionary who attended a seminar that was to help foster peace and religious dialogue between Christians and Muslims in the north. At the end of the gathering, an excited fellow from the audience shouted out: "Who believes in Nigeria?" and almost all the people lifted their hands as they shouted "I!!" Just about the same time, he gave a follow-up question to the first: "Who believes in a Nigerian?" and at this point, one could hear a pin drop. This is something that has been consciously or unconsciously ingrained in our psyche. What does it truly mean to be a Nigerian? The answer is that one is first a member of his/her ethnic group, then a member of his/her religion, then a member of his/her region, then a member of his/her political party and maybe then a Nigerian.

The question of Persecution

Are Christians persecuted in Northern Nigeria? The answer must be put in proper context and this goes a little back into the history of the north. Individual groups defined either by religion or ethnicity assume that their continued existence depends on themselves alone. Belonging, therefore, becomes a matter of either ‘inclusion’ of one or the ‘exclusion’ of another. To belong is also not to belong to the other. In the far north, with the establishment of the Caliphate, the understanding that north was a Muslim ‘umma’ (community or society) renders an exclusive self-definition of the people who belong to such a community, but it also clearly defines, by way of religious identity, those who do not belong to the society. That although this region is part of the wider Nigeria, the quest for self-perseveration of its exclusive identity means the continuous defining of who belongs and who does not by means of inclusion and exclusion. In this case comprehending the nature of religious, political and ethnic interactions, have continued to be shaped by such an understanding. This makes social cohesion in a multilateral context nearly impossible or extremely difficult.

Consequently, on account of a people’s own religion or ethnicity, a sort of indigene/settler divide has come to define how, by default, most communities are defined or organized. The sad outcome of this is that the rights of the minority stand the risk of abuse and privileges and opportunities denied. A person does not belong to a geographical locality that is not his/her ‘ancestral’ home even if they were born and raised all their lives although in the country of their citizenship. Therefore, non-Muslims by an extension of such a notion of identity stratification do not belong in a predominantly Muslim community. In an event where toleration is absent, abuse of rights and denial of privileges, even though provided for in the constitution, are unavoidable.

In most parts of Nigeria, because ethnic and religious affinity still holds strong, people of other ethnic backgrounds are often used as scapegoats or blamed for what is wrong in the community. Christians in the north have been tied to Western imperialism and are often the easy targets for Muslim extremists who want to take a ‘so-called’ revenge attack on the West. During the cartoon crises in Denmark, for example, Non-Muslims in Nigeria, particularly Christians, suffered immense attack as an act of revenge by Muslim fundamentalists who see Christians as western sympathizers and proxies. Jamā'at Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Da'wah wa'l-Jihād nicknamed Boko Haram which means: The forbidding of Western education, projects this animosity towards the west.

It is therefore within this wider matrix and suspicion that the herdsmen/farmers conflict is defined as persecutions of minority Christian ethnic farmers. More so, the nature of the attack has gone beyond the traditionally known herders/farmers conflict to that of armed militia groups attacking mainly non-Muslim and mostly Christian villages leaving behind wanton destructions of lives and communities.

Evidently, these militias are of the Fulani extraction. According to Global terror index, the Fulani militia group is one of the deadliest terror groups in the world. What has further deteriorated the situation is the failure of the government, headed by a president who is both a Fulani and a Muslim, to arrest and prosecute perpetrators of these attacks. The government has been blamed for its silence and this has created a loss of confidence in the government by affected communities.

The President of Nigeria has, in more than one occasion, addressed the issue, blaming it on the Libyan crises. He claims that these militias are people who served Gadaffi and, following his death, have turned to terrorize communities across the West African Region.

Re-thinking nationhood

A way forward for Nigeria and Nigerians will mean an honest return to the concept of National rebirth addressing the question of national identity, equity, fairness and justice. As a matter of National identity, we must come to terms with what truly makes us Nigeria and Nigerians. As a federation, we have to accept the fact that there are different groups and interests. These should not be a deficiency for our country but a strength. Imagine the immense potentials our diversity holds if we see each group and interest as part of the whole and realize that our beauty is in our diversity. When we disagree, it should be for the purpose of constructive progress for all. From the rainforest region to the creeks of the Niger Delta and to the rocky plains of the plateau and up to the hot desert of the North, we are all Nigerians and should not only have the right to speak but be heard wherever we go. In the spirit of true national rebirth, we must decide the most honest way to re-think our governing structure and see ways to truly make our federating units function and give leadership to the Nigerian people.

Nigerians are deeply religious. I do not say this in a derogatory way. It is almost the soul of our country. We display our sense of piety in every area of life. In fact, in times of economic and political turmoil, Nigerians have found great strength and comfort from faith. We revere sacred people and items so devotedly, yet a common sense of valuing human life often defies the peace our "religions" claim to be or give. My faith teaches me a culture of life; that there is such thing as the decency and dignity of human life; that protecting and promoting life is an act of worship to the creator of life. We need to find ways to function as a nation, defining clearly that fine line between state and religion. The idea of keeping the two separate is not godlessness but the way forward for this religiously plural society of ours. It is simply acknowledging that within our society, there are different spheres or institutions and they must each exercise independence for effective functioning. We must have a strong constitution that reflects our collective values and provides for citizens, regardless of their faith and creed, to go on without fear of molestation. Politics should not be used to promote religious agenda nor should religion be used to promote political agenda, be it in the North or South. Political office holders who have sworn to uphold the constitution of the federal republic should be faithful stewards who live by that oath. Should they desire to promote their religion through the means of political office, they should be impeached as abusing the oath of office and the constitution which contains collective guidelines for government operations.

For Further reading

Karl Meir, This House Has Fallen: Nigeria In Crisis (PublicAffairs; 1 edition July 13, 2000)

Niels Kasfelt, Religion and Politics in Nigeria (British Academic Press, 1994)

Yusuf Turaku, Tainted Legacy (Isaac Publishing, 2010)

Matthew Hassan Kukah, Religion, Politics and Power in Northern Nigeria (Spectrum Books Ltd, 1993)

|

|

|

|

|